Scientists find evidence for 'chronesthesia,' or mental time travel

December 22, 2010

Researchers

have found evidence for "chronesthesia," which is the brain's

ability to be aware of the past and future, and to mentally travel in

subjective time. They found that activity in different brain regions

is related to chronesthetic states when a person thinks about the same

content during the past, present, or future.

Researchers

have found evidence for "chronesthesia," which is the brain's

ability to be aware of the past and future, and to mentally travel in

subjective time. They found that activity in different brain regions

is related to chronesthetic states when a person thinks about the same

content during the past, present, or future.

(PhysOrg.com) -- Scientists refer to the brain's ability to think about

the past, present, and future as "chronesthesia," or mental

time travel, although little is known about which parts of the brain

are responsible for these conscious experiences. In a new study, researchers

have used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate

the neural correlates of mental time travel and better understand the

nature of the mental time in which the metaphorical "travel"

occurs.

The researchers, Lars Nyberg from Umea University in Sweden; Reza Habib

from Southern Illinois University in Illinois; and Alice S. N. Kim,

Brian Levine, and Endel Tulving from the University of Toronto in Ontario,

have published their results in a recent issue of the Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences.

"Mental time travel consists of two independent sets of processes:

(1) those that determine the contents of any act of such 'travel': what

happens, who are the 'actors,' where does the action occur; it is similar

to the contents of watching a movie - everything that you see on the

screen; and (2) those that determine the subjective moment of time in

which the action takes place - past, present, or future," Tulving

told PhysOrg.com.

"In cognitive neuroscience, we know quite a bit about perceived,

remembered, known, and imagined space," he said. "We know

essentially nothing about perceived, remembered, known, and imagined

time. When you remember something that you did last night, you are consciously

aware not only that the event happened and that you were 'there,' as

an observer or participant, but also that it happened yesterday, that

is, at a time that is no more. The question we are asking is, how do

you know that it happened at a time other than 'now'?"

In their study, the researchers asked several well-trained subjects

to repeatedly think about taking a short walk in a familiar environment

in either the imagined past, the real past, the present, or the imagined

future. By keeping the content the same and changing only the mental

time in which it occurs, the researchers could identify which areas

of the brain are correlated with thinking about the same event at different

times.

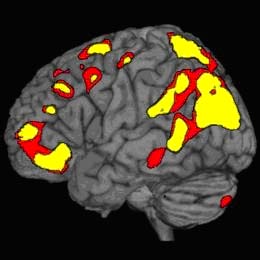

The results showed that certain regions in the left lateral parietal

cortex, left frontal cortex, and cerebellum, as well as the thalamus,

were activated differently when the subjects thought about the past

and future compared with the present. Notably, brain activity was very

similar for thinking about all of the non-present times (the imagined

past, real past, and imagined future).Because

mental time is a product of the human brain and differs from the external

time that is measured by clocks and calendars, scientists also call

this time "subjective time." Chronesthesia, by definition,

is a form of consciousness that allows people to think about this subjective

time and to mentally travel in it.

Tulving said, "The concept of 'chronesthesia' is essentially brand

new. Therefore, I would say, the most important result of our study

is the novel finding that there seem to exist brain regions that are

more active in the (imagined) past and the (imagined) future than they

are in the (imagined) present. He added that, at this stage of the game,

it is too early to talk about potential implications or applications

of understanding how the brain thinks about the past, present, and future.

"Our study, we hope, is the first swallow of the spring, and others

will follow," he said.

Excerpt

from www.PhysOrg.com