A FORM OF WISHING

by Barbara Haskell and John G. Hanhardt

A distinguishing feature of Ono’s performance work was her desire to intensify viewers’ internal awareness and introspective meditation. She facilitated a state of dreaming by paring down visual and auditory stimuli and by concentrating thought on a single idea or isolated perception. “The natural state of life and mind is complexity,” she wrote in 1966; “…what art can offer…is an absence of complexity, a vacuum through which you are led to a state of complete relaxation of mind. After that you may return to the complexity of life again.” Ono’s desire to highlight the stillness of the self by engendering a focused concentration drew on the tradition of Zen meditation practice. Emulating Zen methods, she aimed to free viewers of the mind’s clutter in order to effect a clarity of perception. For example, featured in a program at Carnegie Recital Hall in 1961 was her performance piece A.O.S. which was performed in the dark, in total silence; the only audible sound was the noise produced inadvertently in the process of enacting the performance. She hoped, in this way, to jolt her audience out of the habitual patterns of listening and thinking.

Central to Ono’s work was her attention to intangible forces in nature: in Wind Piece (1962), the audience was asked to move their chairs to make a narrow isle for the wind to pass through; in Sun Piece (1962), she instructed them to “watch the sun until it becomes square.” Typically restricted to short phrases, these events resembled Zen Buddhist koans, whose paradoxical quality was intended to stimulate poetic reveries.

In the spring of 1961, Ono began a group of paints and objects which paralleled her performances in their subject matter and their dependence on chance and audience participation. Ono extended her expansive attitude toward musical sound to mutable visual phenomena by providing the structure of the work—the canvas—but not its specific visual material, which was left to the discretion of the audience.

As conjunctions of object and performance, these works were not static, discrete objects; instead, they embodied notions of becoming and metamorphosis. Like her Events, they exuded a profound respect for organic transformation.

As with her performance scripts and music, Ono’s objects and paintings eliminate visual distractions in an attempt to focus viewers’ concentration. Painting to See the Skies (1961) contained two holes in the canvas through which viewers could see the sky.

Some of these pieces were intended to be completed only in the mind. Her goal in transferring realization exclusively to the imagination was to further the viewers’ sense of wonderment and extend their creative potential—to “allow them to release their inhibitions and allow their own rather nebulous thoughts a freedom of expression.”

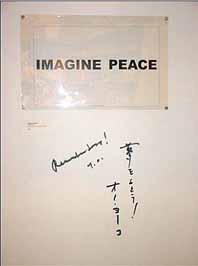

Realizing the potential of this context (popular culture), Ono joined with John Lennon in a number of collaborative projects, such as War is Over (1969), which used their celebrity status to draw attention to the peace movement. Imbued with a pervasive optimism in the power of imagination, these activities manifested Ono’s longstanding belief that the “mind is omnipotent” and that all her work was a “form of wishing.”

[Yoko

Ono (February 18, 1933, Tokyo, Japan) is an internationally recognized

artist, composer, filmmaker, and poet who has been a forerunner of new

art that mixes various media for over 40 years. Ono’s work, influenced

by Dada’s notion of breaking down the barriers between art and life, evolved

to include the mind and thought. Her art relies on the viewers' willingness

to participate in making the art become real through imagination.]