INSIDE A LIFELONG DREAM OF DESERT LIGHT

by Michael Kemmelman

Excerpt from The New York Times 4/8/01

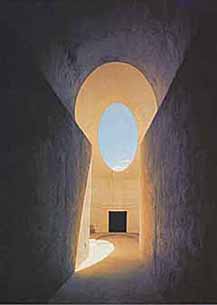

Roden Crater, which James Turrell has been trying for more than 20 years to turn into one of the biggest works of art in the world, is a black and red volcano overlooking the Painted Desert, at the edge of the Navajo reservation 40 miles north of Flagstaff.

Mr. Turrell is not the kind of artist who makes objects to sit in rooms. He creates ambient space. Roden is about the relationship of the tunnels and rooms to the sun, stars and land. It’s about the time you spend, silently looking. It’s about light, or the absence of it, during day and night: you are meant to experience Roden over many hours or, better, overnight in a little lodge he has built into the side of the crater.

His works tend toward meditative elegance. They explore perception, the bottom line of all art; they’re about our watching ourselves look, becoming aware of how we see, not just what we see. “I’m interested in the weights, pressures and feeling of the light inhabiting space itself and in seeing this atmosphere rather than the walls,” is a frequently cited remark.

“I want to address the light that we see in dreams, he says. “It’s not about filling a space with stuff. And light is sensual. Anything sensual, while it can attract you toward the spiritual, can hold you from it, too; it can keep you in the physical world, and that’s an explicit part of my work, which I think is sensual and emotional in the way that music is sensual and emotional.”

And at Roden Crater there are deliberate sound effects: midway up the tunnel your voice projects, as if by ventriloquism, to the elliptical room 400 feet away or, if you turn around, back to the room at the low end of the tunnel-- the Sun and Moon space, as Mr. Turrell calls it. Sound is as important as light: the sounds you make as you walk around but also the near silence of being in such a vast, remote place.

The second phase of the project extends the tunnel into the fumarole to an opening aligned with the sunrise on the summer solstice. Everything at Roden is oriented toward celestial occasions. Every 18.61 years, the moon will briefly align with the tunnel, the next time in 2006.

“I always tell people that my grandmother, who was a Quaker, said to me, ‘Go outside and greet the light.’ But whether that caused me to make art out of light, or whether it affected how I think about light, I can’t say. If you think of all the cathedrals and sacred places in the world, there aren’t many that don’t involve light as a spiritual element.

On a recent afternoon he walked around the crater. The tunnel to Crater’s Eye was pitch black. You had to feel your way along the wall. “My spaces are dim because low light opens the pupil and then feeling comes out of the eye as touch, a sensuous act,” he says.

The room seemed the most peaceful, expectant place on earth. The usual metaphor of a Quaker meeting came to mind while minutes passed. Something about Mr. Turrell’s art, even when it consists just of sitting in a room, switches on a kind of internal light, triggering intangible pleasure.

[James

Turrell (May 6, California, USA, 1943) grew up with a love of aviation

and the sky, as well as a fascination with light. His Quaker background

formed his approach to life and art, with its emphasis on silent access

to the "light within." From age six, Turrell was urged by his

grandmother to "go inside and greet the light" at Quaker meetings.

In the early 1960s, Turrell studied perceptual psychology, mathematics,

geology and astronomy at Pomona College. He also studied in an experimental

program at the University of California at Irvine that combined art and

technology. He began an exploration of the relationship of light and space

that has continued in his work today.]