‘NO

TITLE’

by Marcia Tucker

Excerpt from Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art, edited by Baas and Jacob, 2004

In most art museums, exhibition information is valued over experience—we're encouraged to look at art fast, efficiently, chronologically, linearly (you often can't go back through the show), and it’s packaged for marketing, with an exit through the gift shop.

The impact of Buddhist thought and practice became evident in the late 1960s and early 1970s documented by Lucy Lippard in her classic reference book, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. The premise of this "dematerialization" was the valuing of the idea or concept behind the object, along with the notion that the process of making was more important than the product. In part, this was a reaction to formalism and its emphasis on the object to the exclusion of all else. Artists were interested in multiplicity, ephemerality, art's relation to the everyday, or the concept of the artist as the work of art. A paradigm shift in the understanding of art-making was taking place, a shift that blurred artistic categories and resulted in interdisciplinary work, Happenings, performance art, multimedia installations, earthworks, and the direct engagement of artists with audiences.

The new conceptual and performance-based work required a change of focus, encouraging viewers to become active rather than passive participants in the work of art. This shift was reminiscent of the way that Buddhism encourages practitioners to awaken the potentialities of their own minds, to move past reactive and habitual responses, and to understand that, as Ken McLeod puts it, "we are what we experience." Artistic focus in the late 1960s and early 1970s shifted away from a concern with the integrity, competitive value, and permanence of the art object toward an involvement with the myriad conditions that determine how art is experienced. Looking at art began to require an altogether different quality of attention, a new way of being present to the work, that left many viewers in the dark. Their usual response was (and still is) simply that what they were seeing wasn’t art. Conceptual art, art as language, interdisciplinary performances and events, and ephemeral and non-objective works of art are now commonplace, but the general public has yet to understand what it’s all about.

The beginning of the millennium in many ways resembles the late 1950s, when Buddhism had a strong influence on American cultural life. We’re again living in a period of political and social uncertainty, characterized by a rising tide of materialism, the erosion of democratic ideals and policies, escalating racial tensions, and a widening chasm between the richest and the poorest---a time ripe for renewal of interest in Buddhism. Like the distribution of wealth in America, the art world’s distribution structures afford professional access in the form of exhibitions, reviews, sales, and commissions to an absurdly small percentage of artists working today. In the visual arts in America there are thousands of artists for every reputable commercial gallery on non-profit arts venue, pushing visual and performing artists to find non-traditional ways of showing their work. Some have simply decided not to show their work at all.

While artists will always look for alternatives to traditional venues, the fact that we live in a world where materialism and commercial viability are the norms makes it that much harder.

My favorite artist is Tehching Hsieh, whose life's work consists of in part, five "one-year performances"; and a final piece entitled Earth, which he completed in 1999.

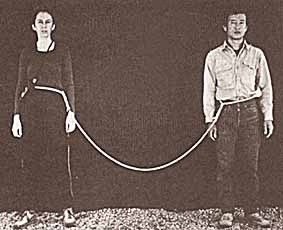

For the first performance (1978-79), Tehching locked himself in a cell in his loft and lived there for a year without reading, writing, speaking, or entertainment of any kind. Twice a day, someone silently brought him food and removed waste. In his second performance (1980-81), he punched a time clock every hour on the hour, day and night, for one year, a witness confirming each day that he had done so. The third piece (1981-82) consisted of living outdoors for a year, never entering an inside space except once, when an altercation landed him inside a police station. In his next one-year performance (1983-84) he was attached to the artist Linda Montano, whom he didn't know, by an eight-foot length of rope. The condition of the work was that they not touch each other for its duration. The Montano piece was followed by a year (1985-86) during which Tehching didn't make, look at, read about or, presumably, think about art at all.

For his final work, he said he was about to begin a thirteen-year piece in which he would make art, but not share it with anyone in any way. Earth lasted from December 31, 1986 to December 31, 1999. Each of these "performances" was a lived metaphor, a sustained act of attention to a basic facet of life—isolation, work, "otherness," intimacy. But his last piece strikes me as a unique act of artistic courage because it involved taking the measure of himself intrinsically rather than extrinsically during his mature years, when people usually look for validation to the outside world. After it was over, Tehching described the piece by saying, simply, “I kept myself alive.” His work intrinsically embodies many of the characteristics of Buddhist practice. That’s part of what makes it so compelling, but it’s also what makes it controversial and difficult for people to understand. Among the most common reactions are, “It’s not art,” and “He’s nuts.” That’s partly because the work is all process, with nothing to show for it. Tehching’s art parallels and exemplifies the Buddhist concept of life, which like a journey, “lies not in the arrival at a certain place but in the progress toward it; in the movement itself and in the gradual unfoldment of events, conditions, and experiences.” (Govinda, Creative Meditation) John Cage, a pioneer in this way of thinking about art, put it this way: “We are not…saying something. We are simpleminded enough to think that if we were saying something we would use words. We are rather doing something. The meaning of what we do is determined by each one who sees and hears it.”

Earth put an end to Tehching's art-making. He now finds traditional art forms too narrow for him, and generally in the service of career, or of "success." Although he no longer works within the parameters of a recognizable art form, Tehching maintains that what he does is still art. He says the artist's life is the work, that it's about human communication, and that "the message is enough."

Tehching's work resurrects time-honored questions about art within our contemporary context: What is a work of art? What is its relation to reality? How can we distinguish between art and non-art? Is it necessary to do so? Buddhism suggests that "the mind is the pre-eminent power in the creation of reality, that through the control of our own thoughts we can create worlds as real as, if not more so, than the'world' which is commonly accepted as the end-all and be-all of daily existence ."

But what happens if a work of art is a life that is being lived? Is it still art? If you take away all recognizable aspects of art as a product, as in the case of Teching’s Earth, what’s left?

One striking parallel between Buddhist practice and artistic practice is that both can jolt us out of our habitual ways of looking at and thinking about the world. Tehching’s work, even stripped of all material evidence, operates on this level. Art really does connect to us on a level outside of language, through what Mark Epstein refers to in Buddhism as “the pleasure of being rather than the pleasure of doing or being done to.” This is the "message" in Tehching's work, work in which there is no artist and no audience, no venue, no viewing experience, no thing. It speaks to us, if it does so at all, in a language resembling that of the poet but without words. And as with a poem, you can't skim read it, you can't describe it accurately, and there's no one way to understand it.

The sense of becoming temporally and spatially untethered while making or viewing art is fairly common, and its affinities to a meditative state are obvious. But many people know that the experience of art can also create a joy that is differentiated from the more elusive sense of pleasure deriving from the pursuit of pleasant physical sensations. If our capacity for joy comes not only from being in the moment, but also "depends on, and supports, the ability to tolerate surprise and unpredictability in one's life," then perhaps joy is a potential outcome of art’s ability to jolt us out of our usual way of seeing. If the mind, the eye, the heart, and the hand are connected—or even more precisely, if they are the same thing—then art also has the capacity to change us altogether. I've heard people use the phrase "the willful suspension of disbelief" to describe the decision to enter a work of art fully. I take it to refer to a conscious letting go of the way we usually experience the world, which is through the intellect, or, as Mark Epstein puts it, "through the filter of...the thinking mind, the talking mind, the mind that is language-based and has developed categories and words for raw experiences.

Of course, joy is hardly the common response to works of art, particularly to difficult contemporary ones. In fact, viewers become discouraged when the thinking mind is of no use to them in this encounter. People think it should be, though, and feel stupid and alienated when they can't understand something through the exercise of their "intelligence." If museums spoke with another kind of voice, one that elicited and valued an experience-based response to works of art rather than an information-based one; if underlying the planning, design, and interpretation of exhibitions was the assumption that there is no one way to look at art and no single correct interpretation of it; then the visual arts might seem a lot less alienating to people. But this would require a radical change in institutional attitudes. If contemporary art were to become a familiar part of people's lives—or at least, if people weren't made to feel that it's an alienating, elitist hoax—then discomfort might turn to delight as imaginations were exercised. We know the solution doesn't lie in more blockbuster shows, bigger and better museum shops, newer and more flamboyant buildings, wings, and renovations, or in putting art collections on the Internet. It is in qualitative, not quantitative, terms that a solution needs to be found.

That's why this seems a good time to explore the parallels between Buddhism and contemporary art. Both are able to move us away from the ideas of permanence, objectivity, independence, and isolation that have characterized institutional attitudes towards art for most of the twentieth century. For example, the solitary viewing experience favored by museums since the late nineteenth century is based on the assumption of individual subjectivity. Buddhism can help to question this assumption, and to identify other ways of being and relating that are based on connection and interaction. Because museums tend to shun the collective, just about the only shared experience in museums today seems to be found in decent tours or elementary school visits. Similarly, the making of art is held to be the business of an individual maker, alone in the studio. Artists who work within communities are seen as community activists rather than “real” artists---especially if they are artists of color.

To

begin to understand that “nothing and no being can exist in itself

or for itself, but only in relationship to other things or beings,"

to know that "just as we cannot be separated from the experiencer,”

would engender a different approach to art altogether. For those of us

in the field of visual arts, even a limited engagement with Buddhist philosophy

and practice could generate a fresh approach to our work, one that would

not (even inadvertently) privilege the institution, isolate the artist,

or demean the public. Buddhism teaches us to relate to the world with

openness, acceptance, generosity, and joy. Could it teach us to relate

to art in the same way?