To see Duchamp as a true believer opposed to the supernatural is to forget

that he had not ceased to interest himself, between the ages of ten and

twenty, and perhaps beyond, in paranormal phenomena. Without a doubt one

must be prudent.

To see Duchamp as a true believer opposed to the supernatural is to forget

that he had not ceased to interest himself, between the ages of ten and

twenty, and perhaps beyond, in paranormal phenomena. Without a doubt one

must be prudent.

Duchamp was too ironic. He cultivated too much skepticism not to be watchful of the reality of these clairvoyant phenomena. He observed them, considered them, believed in them without a doubt always, entirely. However, each time he was interested in them they seemed to be based on a scientific approach that pulled him instantly from his ennui.

In this way, he responded to Arensberg, from whom we know of Duchamp's taste for spirituality and theosophy; in fact, he had once been unconsciously preoccupied by "a metarealism...a need for the 'miraculous' Similarly", after the war he spoke of the artist as a "medium" in a famous declaration, often cited ("Selon toutes apparences, l'artiste agit comme un etre médiumnique qui, du labyrinthe par-dela le temps et l'espace, cherche son chemin vers une clairiere."), and of art as a means of accessing "non-retinal" reality.

Idealism? The romanticism of Novalis? The temptation of a young man for a spiritualism a la Kandinsky, whose writings he conscientiously annotated, even though they are written in a language he little understands? Yes. It was very much this, all of this, that he had gone looking for in Munich in 1912, and it merits our attention. His exemplary copy of Concerning the Spiritual in Art was covered in pencil marks. At the turn of the century, every possible occultist was putting in their two cents about this feeling of intuition that guides the artist blind through "the forest of symbols" of our three-dimensional universe toward a superior reality.

Excerpt

from

"Duchamp at the Turn of the Centuries" by Jean Clair, Paris:

Gallimard, 2000

(translated by Sarah Skinner Kilborne)

Artist as a Parareligious Leader

by Maurice Tuchman

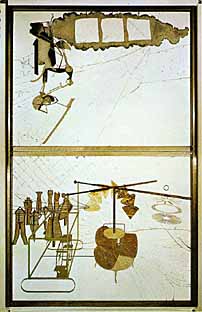

Duchamp's

involvement with the occult, a fascination tempered by his intellectualism,

humor, irony, and detachment, is manifested in much of his work, especially

in The Large Glass, 1915-23. The main visual sources for Duchamp's

interest in nonretinal matters, as first cited by Jean Clair, are the

photographs by Charles Brandt and other photographers presented in Albert

de Rochas d'Aiglun's 1895 volume, L'Extériorisation de la sensibilité,

a compendium of spiritualism and psychokinesis.

Duchamp's

involvement with the occult, a fascination tempered by his intellectualism,

humor, irony, and detachment, is manifested in much of his work, especially

in The Large Glass, 1915-23. The main visual sources for Duchamp's

interest in nonretinal matters, as first cited by Jean Clair, are the

photographs by Charles Brandt and other photographers presented in Albert

de Rochas d'Aiglun's 1895 volume, L'Extériorisation de la sensibilité,

a compendium of spiritualism and psychokinesis.

Duchamp was also influenced by the involvement of his brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon with psychophysiological thought and by Kupka's ideas on spiritualism, which Kupka shared with Duchamp while the two were neighbors in Puteaux in 1901. Duchamp read extensively on alchemy, androgyny (manifested in his Rrose Sélavy persona), the tarot, and the fourth dimension.

He created plastic metaphors from the literature of occult symbolism and insisted on the importance of the artist as a parareligious leader in modern life. During a three-month sojourn in Munich in 1912 Duchamp purchased Kandinsky's On the Spiritual in Art and conceived the plan for his Large Glass. He translated the most important passages of On the Spiritual in Art from German into French, line by line, probably for his brothers, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Jacques Villon, who read no German. The effect of Kandinsky's ideas upon Duchamp merits further investigation.

Excerpt

from: Maurice Tuchman, "The Spiritual in Art, Abstract Painting,

1890-1985", Abbeville Press Fine Art, 1995

[Maurice Tuchman is senior curator of 20th-century art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art]

[Marcel

Duchamp (July 28,1887, Blainville, France-1968, Neuilly-sur-Seine,

France) came from an artistic family. He became one of the most influential

of the Dada artists. Duchamp opposed World War I and identified with Individualist

Anarchism, in particular with Max Stirner's philosophical tract The Ego

and Its Own, the study of which Duchamp considered the turning point in

his artistic and intellectual development. Duchamp was one of the first

artists to use found objects and readymades as the basis for his artworks.]